In our retirement planning, we automatically play it safe. We scale down average growth of 7% and instead plan on spending 4%. We try to pay off a mortgage to own our homes outright, only to leave a legacy. And we are often shy of including our state pension in our calculations.

What if we look at the average case instead? With all the safety margin stripped out.

Let's say that I want to retire with £20k annual spending, and live with my partner in a £300k home. I'm 54, so I'll get my full state pension in 14 years.

We would normally start by saying I need £20k x 25 = £500k invested to give me an income. But hang on, if the "x 25" part of that is reflecting a 4% safe withdrawal rate, in this "average case" example don't we need to change the numbers to account for 7% average growth? That means (...plays with calculator...) we need "x 14.3". That would mean a pot size of £286k instead.

Furthermore, with state pension kicking in to provide £12k income in just 14 years, a part of that pot won't be needed. This is harder to calculate, as it involves a dwindling pot. I'll need a compound interest calculator for this.

I'm aiming to figure out what starting pot size I need for 14 years of £1k per month withdrawals at 7% growth, for this bridging fund until my state pension kicks in. On top of that I'll need a second fund of £8k x 14.3 = £114.4k for that ongoing top-up from a state pension level retirement to a £20k spending retirement.

I'll ignore income tax in these calculations, since it is likely to be negligible. If I'm using a personal pension for most of this saving, £20k of income may mean under £700 per year of income tax.

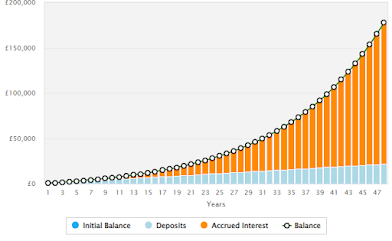

Here's the compound calc result:

It thinks I'll need a pot of £107k for the heavy lifting part of the plan.

£107k + £114.4k = £221.4k investment pot needed.

Finally, there's the house to pay for. Here there's another way to pare down the capital needed. We normally project to have our house paid off, leaving the capital in it as a safety margin which could be used for equity release or as a legacy after we're gone. Let's juice it instead.

We can use equity release to free up a maximum of 70% of the capital in our home. For ease of maths let's call that 66% and say that I only need £50k invested in my half of the £300k house.

All together this means I need a net worth of £271.4k to retire at 54 with a £20k spending level.

We had started out thinking I needed £500k invested + £150 house equity, so a net worth of £650k.

Remember, this is an "average conditions" plan. We've been applying a safety margin of 2.4x to our plans.

Conclusion

Certainly there is some safety margin needed. We could hit a poor sequence of returns with a stock market crash early in retirement. Or we could have unplanned spending, such as care home costs, which eat into the pot enormously. And certainly juicing the house equity won't suit everyone. But this does go to illustrate how much padding we normally apply.

If your numbers are anything like approaching these ones, you may be reassured to learn that you're actually finished with building your necessary pot of net worth, and are on the final task on adding the safety margin.

Want to read more of my ideas? I have a new book out - Build Your Retirement, 5 ways to improve your wealth in retirement.